The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Review by Maureen Hanes.

The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is a part journalistic investigation, part memoir that explores the history of the gulag system in the Soviet Union and documents what it would have been like to experience the system firsthand. The book was first published in three segments in 1973, 1974, and 1976 respectively by the French publisher Editions du Seuil, as the book could not be published in the Soviet Union at the time. English translations of each segment followed in 1974, 1975, and 1978 published by Harper and Row, and the first abridged version in English was published in 1985 (“The Gulag Archipelago”).

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a Russian author who, in 1945, was arrested and sentenced to eight years in a camp for criticizing Stalin in a letter to a friend. His term in camp was followed by permanent exile, though his time in exile ended with reforms under Khrushchev in 1956. In 1962, with permission from Khrushchev, he was able to publish his famous work, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, but in 1968, he was expelled from the Soviet Writer’s Union during a period of increased censorship and was forced to publish The Gulag Archipelago outside of Russia (“Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn.”; “Biography”).

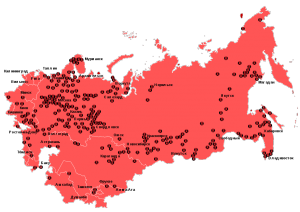

The Gulag Archipelago is broken into seven sections, with each exploring a different aspect of the gulag system. The sections move chronologically through history as well as through the experience of an arrested person. The first section discusses the process of arrest and interrogation and the second of the process of arriving at the camps. The third section then explores life inside the prison camps and the fourth explores the effects of the camps on the souls of prisoners. The fifth section explores an especially brutal type of labor camp, the Katorga, as well as resistance efforts by prisoners, while the sixth discuss life outside of the camps in exile. The last section provides a conclusion for the book, with Solzhenitsyn reflecting on the place of gulags within the Soviet Union. Much of the information presented was gathered by Solzhenitsyn through letters, writings, and 227 interviews with other former gulag prisoners; however, throughout the book, Solzhenitsyn also refers back to his own experiences. To connect the different sections of the book, Solzhenitsyn uses a variety of literary devices. One example is his use of an archipelago as a metaphor to describe how the gulag system worked, with individual camps scattered throughout the Soviet Union all connected by the same underlying system of violence, fear, and forced labor.

One of the main themes that Solzhenitsyn focuses on throughout the work is that exposing the truth about the gulag system and committing it to memory is necessary in order for people to process the trauma of the system and prevent future atrocities. Solzhenitsyn saw gulags as an almost logical extension of the repression of the Soviet system and made comparisons to other similar phenomena in the 20th century, such as Nazi concentration camps. Unlike in Nazi Germany, however, Solzhenitsyn pointed out that there had been nothing in the Soviet Union like the Nuremburg Trials, leaving Soviet citizens without any similar sense of justice and remembrance. Solzhenitsyn writes, “In keeping silent about evil… we are implanting it, and it will rise up a thousandfold in the future,” (81). Another theme that Solzhenitsyn focuses on is the idea that all humans have the capacity for both good and evil within them. Throughout the work, he provides examples of everyday people betraying their friends or neighbors to authorities out of fear and, in contrast, prisoners in horrific circumstances continuing to produce art and poetry, and writes:

“Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, no between political parties either – but right through every human heart …And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains… an unuprooted small corner of evil,” (Solzhenitsyn 312).

One chapter that I found particularly moving from the book was from the fifth section, Chapter 12: “The Forty Days of Kengir”. This chapter documents the most successful uprising in the history of the gulag system: the Kengir uprising. The uprising was sparked by multiple killings of innocent prisoners by guards, and after a series of unsuccessful small protests, the prisoners eventually banded together to drive out all the guards and create their own self-government for forty days. Although the uprising was ultimately brutally suppressed by the Soviet military, it represented the longest lasting protest against Soviet authorities within the gulag context. This chapter stood out to me as one of the most hopeful in the book, even despite the tragic end to this story, as it showed that victims of the system did not always passively accept their fate – their very desire for freedom could not be completely stamped out by the gulag. I found the following quote a stirring example of how much humanity prisoners could still retain even in the worst circumstances:

“Mutinous zeks! These eight thousand men had not so much raised a rebellion as escaped to freedom, though not for long! …The morning of May 19 dawned over a feverishly sleepless camp which had torn off its number patches. Many took their street clothes from the storerooms and put them on. Some of the lads crammed fur hats on their heads; shorty there would be embroidered shirts, and on the Central Asians bright-colored robes and turbans. The grey-black camp would be a blaze of color.” (Solzhenitsyn 408).

In terms of emotional appeal, this book is extremely moving and encourages the reader to think deeply about their own ideas of good, evil, and humanity in general. The book also provides and extremely detailed historical narrative of the gulag system, and Solzhenitsyn provides plenty of research and evidence to back up his own narrative with the experiences of others. There are times when he admits that certain stories or statistics cannot be known for certain, but I find his honesty actually helps his argument. The organization of the book can occasionally be hard to follow, but this is likely due to the fact that Solzhenitsyn was never able to review the entire transcript at once because of security concerns.

For the average reader, I think this book is rather unwieldy, as even the abridged version is almost 500 pages and extremely dense; though for those seeking to study gulags in depth, I would highly recommend it. As Ericson writes in the Introduction, the work was written “by a Russian and primarily for Russians… It is these readers in particular who need to know in as much detail as possible the truth of their history…” (Solzhenitsyn xiii). While these efforts may have been hindered by Solzhenitsyn’s inability to publish this book in the Soviet Union, even for an international audience, the book provides a detailed look at the gulag system and experience and serves as a powerful warning to how easily state repression can lead individuals to act fearfully and violently towards one another.

Works Cited

“Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aleksandr-Solzhenitsyn.

“Biography.” The Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Center. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.solzhenitsyncenter.org/his-life-overview/biography.

“The Gulag Archipelago.” The Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Center. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.solzhenitsyncenter.org/his-writings/large-work-and-novels/the-gulag-archipelago#:~:text=The%20three%20volumes%20of%20The,in%202018%20by%20Vintage%20Classics.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-56: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. Abr. ed. Translated by Thomas P. Whitney, Jr. and Harry Willets, Jr. Abridged by Edward E. Ericson Jr. London: Harvill Press, 2003.